As an ESL teacher, I often get the opportunity to notice some of the differences between English and other languages (usually resulting in English being a very hard language to learn—friendly reminder to give a shout-out to any English language learners you know!). We have such a rich vocabulary, in part because so much of our language comes from so many other languages, and also because English has been around and been spoken increasingly widely for so long that it’s changed and evolved significantly over time. This richness is a blessing and a curse—it makes the language that much more difficult to learn, but also lends it to some pretty amazing possibilities in communication and literature.

So, with this richness of vocabulary, it’s surprising to me that we manage to make it by with only one word for love (whereas many other languages have several). The love I’m referring to when I say, “I love cheesecake” is clearly very different from the love I mean when I say, “I love my kids.” And that love is still quite different from the romantic love I’m talking about when I say, “I love my husband.” In Spanish, for example, you’d likely use a completely different verb for all of these situations.

I’ve been thinking about the kind of love God says that He has for us.

God’s love is unconditional. I’ve seen some pushback on this idea recently, and I think it’s because people are concerned about the idea that God doesn’t care about the choices we make in our lives. I believe that’s a valid concern; scriptural text, oral tradition, and logic all seem to indicate that a divine parent would care about the choices we make—the way we treat others (especially considering those others are His children too) as well as the personal choices that He knows will either help or hurt our ability to grow, progress, and be happy long-term.

However, I think it is just as dangerous, and probably more so, to start thinking of God’s love as conditional. He may not always love our choices, but He always loves us. We may also struggle—because of our choices, or simply because of hardship—to feel His love, but that doesn’t make it any less there. He sees our immense potential, and because He loves us, He is not going to be satisfied with leaving us where we are. And yet He isn’t waiting to love us. He loves us where we are, warts and all.

God’s love is sometimes tough. He says that he chastens those He loves. We can feel that chastening when we make bad choices and experience the consequences, including the feeling of guilt. We also feel it when we experience trials that aren’t our fault, but He which allows. In some cases, He allows trials to teach and shape and refine us. In others, He’s looking out for us and protecting us from some future harm that we can’t see. He also gives us the agency to make our own choices, which means we’re susceptible to the pain caused by the choices of others—and they are susceptible to pain caused by our choices. And sometimes, I wonder if He must allow our suffering because of a bigger plan that we can’t see, one that is much bigger than our individual lives or our ability to comprehend, and we won’t get those answers until after this life.

At the same time, God’s love is full of tender mercies. He fills the earth with reminders of His love. He puts beauty, experiences, and people in our lives that He knows will bring us joy. I believe some of those tender mercies are by cosmic design, but I wouldn’t be surprised to find out that some of them are “just because” He wants to see us happy, even for a moment.

God’s love is selfless. I wonder what kind of pain is involved in being God. He is constantly aware of all of us, and at any given moment there is nearly immeasurable suffering going on in the world. There are times He intervenes and times He doesn’t, for reasons we may not understand, which must be incredibly difficult. And yet He doesn’t shy away from the complexity, the grief, the frustration, and the sorrow that comes from loving us. Somehow, He has figured out a way to find enough joy to keep going—and I think He is trying to teach that to us.

I’ve had a few moments lately to see evidence of my own love under a bit of a microscope, and uncomfortably found it lacking.

I think that my love is unconditional, and yet I feel myself pulling away when I don’t like someone else’s choices. To clarify, I’m not talking about removing myself from an abusive situation; I believe that’s simple necessity and is, in and of itself, a show of love for both ourselves, who are God’s children, and even for abusers, who are also God’s children and must learn and grow by feeling the natural consequences of their actions. I’m talking about allowing loving thoughts to be replaced with critical, vengeful, or judgmental thoughts because someone’s choices make me feel defensive. I’m talking about catching myself wanting someone’s choices to backfire because I hope to be proven right. I’m talking about feeling the frustration, disappointment, or anger which is natural when someone makes a bad choice, but which becomes problematic when it’s empty of the empathy and patience that I would want to be afforded for my own bad choices.

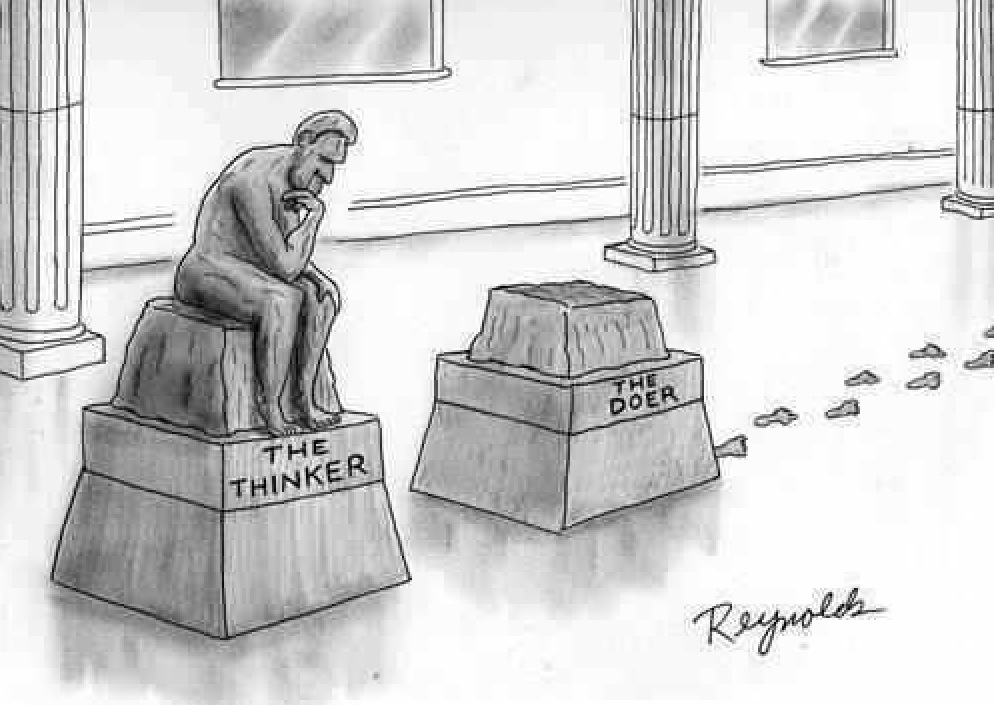

I think that my love is tough (at least, when necessary), and yet I shy away from opportunities to offer help and advice or share opinions if I don’t think they’ll be welcome. In other situations, I struggle to let go of the impulse for control and to allow others to make their own decisions and feel their own pain (whether related to decisions or not) with the trust that things will work out. There’s a conflicting balance to be found between these discomforts, but it’s a balance worth finding.

I think that my love is tender and merciful, but I miss so many chances to do the small things that show my love to others. I take it for granted that they know I love them, and then I occasionally get a painful reminder that they may not always feel that.

I think that my love is selfless, but then find that some of the reason I struggle to love more fully is because my love for others is centered on myself. I want to be loved back; I want to be thought of in a certain way; I take the choices of others personally; I want to avoid the awkwardness or potential hurt that comes with feeling and showing love.

A lot of these reflections have come in parenting. It’s amazing how parenting exposes all kinds of things we didn’t realize about ourselves, in a raw and simple way. But other moments have been more nuanced—moments in my marriage, extended family relationships, and even relationships with friends and acquaintances. It’s humbling to see how much there is to learn when we start looking.

Wishing you all a (belated, as usual) happy Valentine’s Day, and hoping to learn to love more fully going forward. I hope those of you who read this and know me know that—though it’s an imperfect love—I love you!